In the work I do with men, I have noticed how easily we become obsessed with winning the affirmation of others. In the process, we get personal achievement confused with our value and worth as men. Therefore, for most men today, life is all about “what I do” and how successful I am at “what I do.” Unfortunately, this approach to life has the potential to be quite destructive.

You may remember the story of Kathy Ormsby. Ormsby was a premed honor student at North Carolina State University. She also happened to be the collegiate record holder in the women’s ten-thousand meter run. The day came when she had at last achieved her dream of running in the NCAA track and field championship in Indianapolis. She was heavily-favored to win.

Something quite unexpected, however, happened during this race. Ormsby fell behind and couldn’t seem to catch the frontrunner. In a startling move after the race, she ran off the track and out of the stadium to a nearby bridge where she jumped over the side. The forty-foot fall permanently paralyzed her from the waist down.

When we equate our worth as human beings with our individual performances, we put our identities at grave risk. Any type of perceived failure from the perspective of an ego built on such a shaky foundation can easily lead us to conclude that our lives are not worth very much.

Tim Keller goes so far as to suggest that “we are the first culture in history where men define themselves solely by performing and achieving in the workplace. It is the way you become somebody and feel good about your life.” Keller adds that he believes “there has never been more psychological, social, and emotional pressure in the marketplace than there is at this very moment.”

When we find our identity, our sense of worth, from someone outside of ourselves, we allow them to participate in the shaping of our identities. Once we conform to the standards of this audience, we let them determine how well we are doing in our assigned role and define how successful we are in life.

I readily admit there is an audience out there that powerfully influences who I am and how I measure up. The same is true for most men. And though we may not like it, we yearn for their approval. We want to exceed their expectations. Doesn’t this beg the question: Who is my audience, the people whom I have empowered to determine my value and worth as an individual?

Charles Cooley, a prominent and highly respected sociologist who lived from 1864 to 1929, came up with a landmark concept called “the looking-glass self,” a human development which remains valid today. In its simplest form, the theory states:

A person gets his identity in life based on how the most important person in his life sees him.

For a child, of course, that person is a parent. We all know how important it is for parents to encourage and build their children because we have such an impact on their sense of worth as they develop. However, as the child grows up and becomes a teenager, the parents inevitably discover they are no longer their child’s number one audience. Most parents, for better or for worse, have been almost completely replaced by the child’s peer group. Most teenagers value the opinions of their friends above all else. Few of us adults would argue that anything but peer pressure is the most powerful force in the life of a teenager.

For an adult, particularly an adult out in the workplace, the opinion valued the most will typically come from a colleague or peer. We greatly value what other men and women in the workplace and in the community think of us. They are our audience, and we perform for them. We yearn to hear their applause.

And sadly, whether we are a teenager or an adult, we often unconsciously allow our audience to deliver the final verdict as to the value of our lives. The reality, however, is that the verdict is not “in” because the performance is never over. No matter how much applause we received yesterday, we can’t be certain we will receive it again tomorrow.

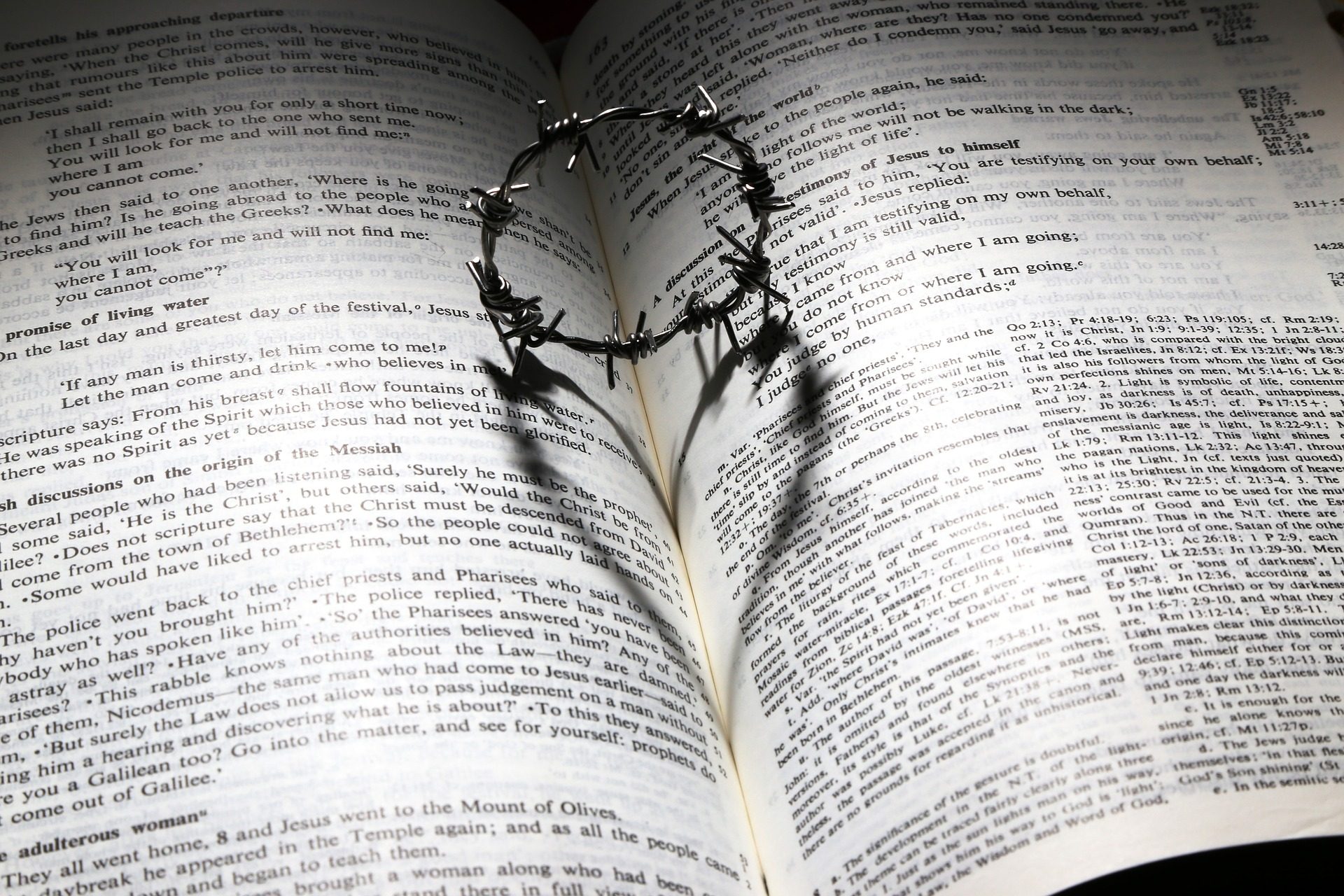

But what do you think would happen if Jesus Christ were the most important person in a man’s life? If He were the audience whom we sought to please the most? I contend that it would change everything. Jesus loves us with an everlasting love, and His love is not based on my performance or my level of achievement.

This is what happened to C. S. Lewis when he converted from atheism to Christianity. In Christ he found a new identity. He described it as “coming to terms with his real personality.” Furthermore, Lewis said, “Until you have given yourself up to Him, you never find your true self.”

Therefore, if Cooley is correct, and that we get our identity in life based on how the most important person in our life sees us, we must honestly ask the question: who is the most important person in my life? Whom am I seeking to please the most? The answer to that question means everything, and it will determine the ultimate course of my life.

Add grace and understanding to your day with words from Richard E. Simmons III in your inbox. Sign-up for weekly email with the latest blog post, podcast, and quote.

For local orders in the Birmingham, AL area, enter Promo Code LOCAL at checkout to save shipping. We will email you when your order is ready for pickup.

Bulk discounts for 25 or more books! Call 205-789-3471 for prices.